The gates are chained, the barbed-wire fencing stands,

An iron authority against the snow,

And this grey monument to common sense

Resists the weather. Fears of idle hands,

Of protest, men in league, and of the slow

Corrosion of their minds, still charge this fence.

Beyond, through broken windows one can see

Where the great presses paused between their strokes

And thus remain, in air suspended, caught

In the sure margin of eternity.

The cast-iron wheels have stopped; one counts the spokes

Which movement blurred, the struts inertia fought,

And estimates the loss of human power,

Experienced and slow, the loss of years,

The gradual decay of dignity.

Men lived within these foundries, hour by hour;

Nothing they forged outlived the rusted gears

Which might have served to grind their eulogy.

An Abandoned Factory: Detroit

Phillip Levine, 1928-2015

Pulitzer Prize Winner, Poet Laureate, Detroit Native

Abandonment: homes now hollow; stores now desolate; factories now impotent; people now invisible. This is the aftermath of life in and around the Poletown neighborhood in Detroit after the construction of the General Motors Hamtramck Plant, also known as the Central Industrial Park Project (CIPP) with one-third of the neighborhood simply gone, reimagined as concrete and emptiness. To be clear, desolation, blight, crime, and abandonment were present before the battle for Poletown took place. In this instance, however, the sting of defeat seemed to amplify the despair and the massive demolition drove home what many in the lower ends of the economic system in America already know: to some in power, there are communities who are seen as expendable.

Past blogs addressed the history and events of Poletown within the context of power structures and policy, including issues of race, class, and eminent domain. The overarching theme of the CIPP and what happened to the Poletown neighborhood rest squarely within the realm of economics. This article will touch briefly on the economic culture of the early 1980’s and how the call for a new economic analytic framework could serve to mitigate similar situations in the future. But the idea of economics fails to address the reality of the people affected by such decisions. For this reason, this article will also address the people of Poletown within the context of a trauma-informed framework and will conclude with how art can be utilized as a vehicle for both resiliency in the face of trauma and social action.

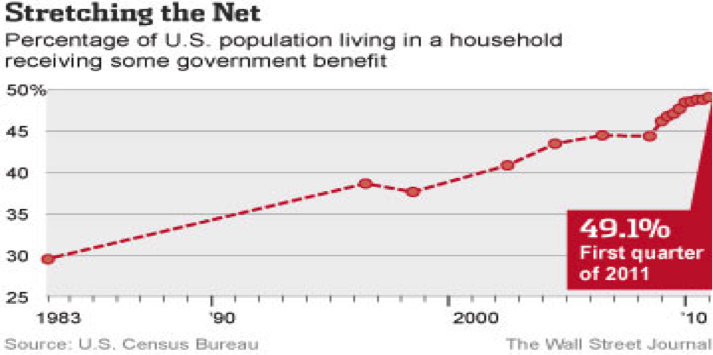

In the United States in the early 1980’s, Ronald Regan was President and, under his administration, the 1981 Economic Recovery Act has been touted as one of the main factors in boosting the American economy with tax cuts for individuals and reduced tax burdens for corporations and business (Mitchell & Fellow, 1991). Some of the premises behind this policy (and subsequently something proponents of the plan point to as confirmation of its success) include the ideas that when wealth increases for those in the upper socio-economic sector, it also increase for those on the low end; cutting taxes on the wealthy actually increases their tax obligation; and social programs are a detriment to economic growth (Mitchell & Fellow, 1991). Supporters of the 1981 Recovery Act point to statistics regarding economic growth rates for all Americans, including families in the bottom 20 percent, noting a decline by 12.7 percent in income prior to 1981 and a rise by 11.9 percent between 1982 and 1989 (Mitchell & Fellow, 1991). While this is seen as an increase on paper, the families, with little financial stability to begin with did not realize, in daily life, the economic boon characterized by Regan’s economic proponents as revealed when looking at the need for government assistance and the fairly consistent level of those with income below 50 percent of the poverty line (see Figures 1 & 2).

Figure 1

Figure 1. Government benefit for U.S. citizens; note the steady increase starting from the early 1980’s (Regan economics) to 2010 (Plummer, 2012).

Figure 2

Figure 2.. Note the consistency between 1980 and 1990, with 1980 and 2000 rates being similar (Eichelberger, Lee, & Vicens, 2014).

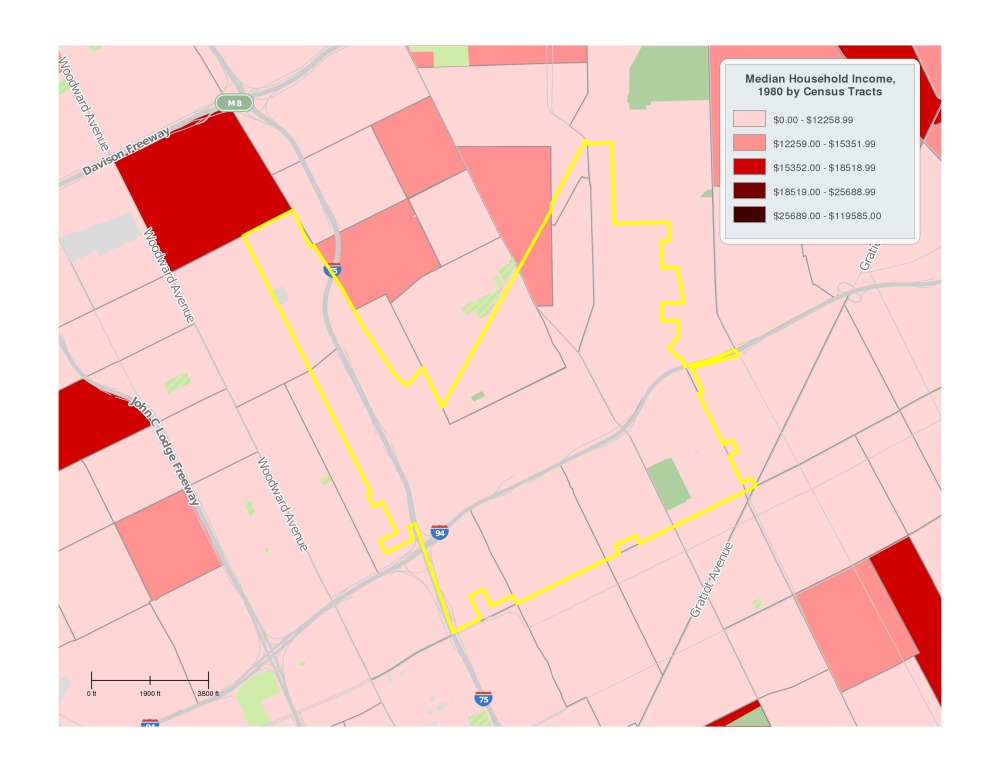

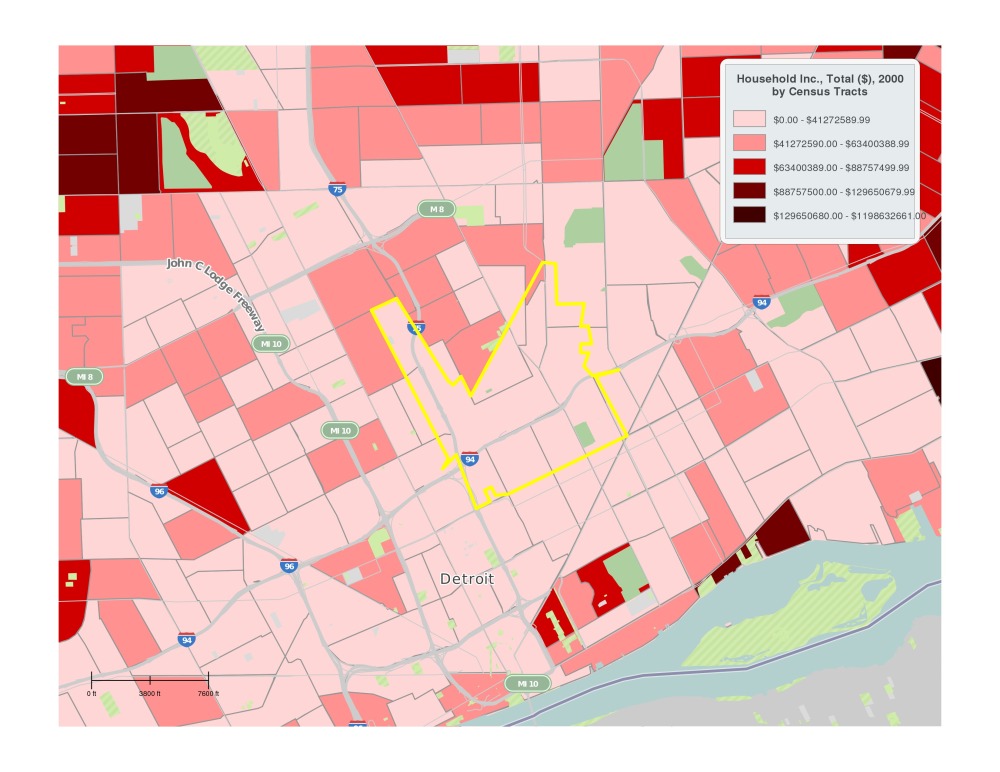

While it may be true that those in middle and upper socio-economic groups felt the impact of economic policy in the early 1980’s, those in the low end did not and those in the Poletown neighborhood remained economically stagnant.

Figure 3. 1980 Median Household Income for Zip Code 48211

Figure 3. Median household income for residents of Poletown East in 1980

based on U.S. Census data; map created using Simply Map software program.

Figure 4. 2000 Median Household Income for Zip Code 48211

Figure 4. Median household income for residents of Poletown East in 2000

based on U.S. Census data; map created using Simply Map software program.

With the explosion of technology and resulting growing awareness of social and cultural issues and impacts on the community, state, and global levels, developing economic frameworks seek to offer a more comprehensive view of economics. Jing and Tao (2017) advocate for a comprehensive, analytic framework for economic policy that takes into account the complexities and interplay of diversity within organizations and institutions and call for polycentric governance. Throsby (2001) examines the interplay between economics and culture, arguing economic activity takes place within a cultural environment and calling for the inclusion of culture in economic policy-making. These new trends in economic policy show some promise in mitigating the plight of those, like the Poletown residents in the 1980’s, who remain consistently at the bottom of the socio-economic pool, left to rely on government assistance and often work to simply survive without hope of ever getting ahead, stuck in conditions where basic needs are often inconsistently met.

Much has been written in the past few decades about the development, implications, and implementation of a trauma-informed framework related to impoverished urban populations at all ages. Studies have focused on trauma in urban areas related to adults (Parto, Evans, & Zonderman, 2011) and children (Becker, Greenwald, & Mitchell, 2011; Parson, 1994). Other studies focused on the impact of trauma on youth in the welfare system (Conners-Burrow, Kramer, Sigel, Helpestill, Sievers, & McKelvey, 2013; Kisiel, Fehrenbach, Torgersen, Stolbach, McClelland, Griffin, & Burkman, 2013); homeless youth (McKenzie-Mohr, Coates, & McLeod, 2012); and implications for school and learning (Cook-Cottone, 2004; Overstreet & Mathews, 2011; West, Day, Somers, & Baroni, 2014). The concept of historical trauma (HT) has been more narrowly researched in relation to colonialism and indigenous peoples, specifically American Indian and Alaska Native populations (Prussey, 2014). For the purposes of this paper, trauma will be applied in recent historical context (within the past few decades), however one should note that trauma can compound over an individual lifetime and across generations.

Trauma is defined as an emotional response to a terrible event where denial and shock, including physical symptoms, are typical responses (American Psychological Association, 2017). Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) “is an anxiety problem that develops in some people after extremely traumatic events, such as combat, crime, an accident or natural disaster. People with PTSD may relive the event via intrusive memories, flashbacks and nightmares; avoid anything that reminds them of the trauma; and have anxious feelings they didn’t have before that are so intense their lives are disrupted” (American Psychological Association, 2017). Several studies have focused on the effects of trauma on the residents of Detroit. In one study of over 2,000 adults aged 18-45, researchers found the highest risk of PTSD for victims of assaultive violence, the sudden unexpected death of a loved one as the most common precipitating event in the development of PTSD, and a higher incidence of PTSD in women versus men (Breslau, Kessler, Chilcoat, Schultz, Davis, & Andreski, 1998). Two other studies explored the correlation between PTSD and Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) and found that early treatment of either disorder mitigated the development of the other, persons with PTSD and/or MDD had an increased risk of physical diseases, and study participants experienced high rates of lifetime exposure to trauma (Horesch, Lowe, Galea, Aiello, Uddin, & Koenen, 2017; Nevell, Zhang, Aiello, Koenen, Galea, Solvien, Zhang, Wildman, & Uddin, 2014). These specific studies are included to paint the broad picture in which trauma and its effects are and have been the reality for many in the Detroit community.

In the Oxford English Dictionary (2017), the word “community” has several similar, yet nuanced definitions, all involving some type of connection. Those who chose to dismantle the Poletown community might have defined Poletown as a community, yet the notion of community value did not seem to factor into their decision-making. Former Poletown residents attempted to express value of community when asked about what they missed most about their old homes. The number one item identified for 78% of former residents over 60 years of age and 51% of those aged 18 to 59, involved an aspect of community; either neighbors, church, or friends (United States General Accounting Office, 1989). Given Poletown residents’ history of integration, generational ties, and self-identification of regret over its loss, community for these people cannot be defined without the inclusion of meaning within the context of quality of life. These people were interconnected, sharing their lives with one another whether on purpose or by default.

Brown (2017) asserts that human connection is our reason for being; humans are hard-wired for connection. If this is so, it stands to reason that community, especially generations old, deeply entrenched community, plays an invaluable role in the wellbeing of its members. Trauma, as noted, has been familiar to some in urban areas across the United States and to some in Detroit in particular. Given the loss experienced by the residents of Poletown, the dismantling of community can be described as a traumatic event with similar impact as any other trauma.

One way to address trauma is through art therapy, both structured and unstructured, group and individual (Hass-Cohen & Findlay, 2015; Lande, Tarpley, Francis, & Boucher, 2010; Levine, 2009; Waller, 1993). The creation of art and use of art therapy have also been linked to social action and change (Kaplan, 2007; Levine & Levine, 2011). One interesting and poignant example of art as both communal therapy and social activism is the Heidelberg Project.

The Heidelberg Project is a dynamic art installation spanning two blocks in a blighted Detroit neighborhood. Created in 1986 by painter, sculptor, and urban environmental artist Tyree Guyton, the mission of the project is “to inspire people to appreciate and use artistic expression to enrich their lives and to improve the social and economic health of their greater community” (Heidelberg Project Mission, www.heidelberg.org). The art community spans two urban blocks, including Heidelberg Street, project namesake, and incorporates houses, empty lots, and found objects to create the installation. Abandoned buildings are re-imagined as provocative statements, abandoned toys now act out tales of oppression, and abandoned lots now hold questions in the form of clocks, doors, and vinyls.

Abandonment was a theme at the beginning of this article and remains a theme in Detroit. But abandonment and emptiness do not paint the whole picture. This author recently travelled to the Poletown neighborhood and surrounding areas. The following are the author’s personal impressions and experiences, along with photos of the visit to the Heidelberg Project.

What at first glance seems like nothingness, empty, abandoned, and vacant is mostly true of the GM Plant itself. Chain-link fencing surrounds acres of flat land; concrete, barren, lifeless. One must look closely at the remnants of neighborhood around the factory, but there are true signs of life. There is an existence, a reality for those left in the Poletown neighborhood and its surrounding areas. Graffiti, art in its own right, makes a statement, “I was here;” a house nestled between an empty manufacturing company and a struggling ministry with a strand of brightly colored artificial flowers on the fence next to a “Clinton-Kaine 2017” sign; a lone person wearing pajama bottoms, boots, and a winter coat scampering across a relatively busy intersection, darting between cars; and even trash: a McDonald’s wrapper dancing in the wind is an artifact from someone’s meal. These visual elements, minute, colorful disruptions to an otherwise bleak canvas set the scene for what was to come: The Heidelberg Project.

The Artist and The Author “Dot House” Window

Superman Pose The Real Superman

“Smooth” by Tyree Guyton Heidelberg Project Demonstration

Two Sides of the Same Piece

Who Are YOU and What Are YOU Doing?

Who Are YOU and What Are YOU Doing?

Bench at the Entry of the Heidelberg Project

Bench at the Entry of the Heidelberg Project

Alarming Juxtaposition

Car Graveyard

For A Good Cause

One of the most striking elements of the Heidelberg Project is its resiliency in the face of adversity, not unlike the people of Detroit. The final blog in this series will examine current growth trends in the Detroit as well as how these new trends impact the most vulnerable members of the community.

Somewhere in the

Projects. There’s a kid working

On a project. To project

To the world. He lives

in a city that Grows

boys and girls into Lions

and tigers. A city that takes

the fire and the ashes

builds rebuilds

turns abandoned houses and

empty fields into things worth

looking at. A place that never looks back

The center stage of

a nation the heartbeat

the patience the music

The Motown the midtown

the downtown

the always comes back

around. Where we fight for our reputation

Walk ride bike to our

destination. Practice patience

Knows that they can’t forget about

- Detroit

the city that continues to call

the worlds bluff

somewhere there’s a kid working

on a project. To project

From a city that’s

rebuilding. That we building from

the ashes together

so that everywhere there can be

Detroit.

I Belong Here

Natasha P. Miller, Detroit Native

References

Becker, J., Greenwald, R., & Mitchell, C. (2011). Trauma informed treatment for

disenfranchised urban children and youth: An open trial. Child and

Adolescent Social Work Journal, 28, 257-272. doi: 10.1007/s10560-011-

0230-4

Breslau, N., Kessler, R.C., Chilcoat, H.D., Schultz, L.R., Davis, G.C., & Anderski, P.

(1998). Trauma and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder in the community:

The 1996 Detroit Area Survey of Trauma. Archive of General Psychiatry,55,

626-632.

Brown, B. (2017). Research. Retrieved from: http://brenebrown.com/research/

Community. (2017). English Oxford Living Dictionaries. Oxford University Press.

Retrieved from: https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/community

Conners-Burrow, N.A., Kramer, T.L., Sigel, B.A., Helpenstill, K., Sievers, C., &

McKelvey, L. (2013). Trauma-informed care training in a child welfare

System: Moving it to the front line. Children and Youth Services Review, 35,

1830-1835.

Cook-Cottone, C. (2004). Childhood Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Diagnosis,

treatment, and school reintegration. School Psychology Review, 33(1), 127-

139.

Eichelberger, E., Lee, J., & Vicens, J. (2014). How we won-and lost-the war on poverty,

in 6 charts. Mother Jones. Retrieved from: http://www.motherjones.com/ politics/2014/01/charts-poverty-50-years-after-war-poverty

Horesh, D., Lowe, S.R., Galea, S., Aiello, A.E., Uddin, M., & Koenen, K.C. (2017).

An in-depth look into PTSD-depression comorbidity: A longitudinal study

of chronically-exposed Detroit residents. Journal of Affective Disorders, 208,

653-661.

Jing, Y. & Tao, W. (2017). A new analytic framework on mainstream economic

system in complex reality. China Economist, 12(2), 114-123.

Kisiel, C.L., Fehrenback, T., Torgersen, E., Stolback, B., McClelland, G., Griffin, G. &

Burkman, K. (2013). Constellations of interpersonal trauma and symptoms

in child welfare: Implications for a developmental framework. Journal of

Family Violence, 27, 1-14. doi: 10.1007/s10896-013-9559-0

Lande, R.G., Tarpley, V., Francis, J.L., & Boucher, R. (2010). Combat Trauma Art

Therapy Scale. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 37, 42-45.

Levine, P. (n.d.). An abandoned factory: Detroit. Poem Hunter. Retrieved from: https://www.poemhunter.com/poem/an-abandoned-factory-detroit/

McKenzie-Mohr, S., Coates, J., & McLeod, H. (2012). Responding to the needs of

youth who are homeless: Calling for politicized trauma-informed

intervention. Children and Youth Services Review, 34, 136-143.

Miller, N. (2017). I belong here. The Journal: An Editorial Hub Dedicated to the

Spirit of Shinola. Retrieved from https://www.shinola.com/thejournal

/people/profiles/detroit-poet-natasha-t-miller-speaks-her-love-motor-city

Mitchell, D. J. & Olin Fellow, J. M. (1991). Tax rates, fairness, and economic growth:

Lessons from the 1980s. Backgrounder, 860, 1-12. Retrieved from:

http://s3.amazonaws.com/thf_media/1991/pdf/bg860.pdf

Newell, L., Zhang, K., Aiello, A.E., Koenen, K., Galea, S., Soliven, R., Zhang, C., Wildman,

D.E., Uddin, M. (2014). Elevated systemic expression of ER stress related

genes is associated with stress-related mental disorders in the Detroit

Neighborhood Health Study. Psychoneuroendrocrinology, 43, 62-70.

Overstreet, S. & Mathews, T. (2011). Challenges associated with exposure to

chronic trauma: Using a pubic health framework to foster resilient outcomes

among youth. Psychology in the Schools, 48(7), 738-754.

doi: 10.1002/pits.20584

Parson, E.R. (1994). Inner city children of trauma: Urban violence traumatic

stress response syndrome (U-VTS) and therapists’ responses. In J.P. Wilson

& J.D. Lindy (Eds.), Countertransference in the treatment of PTSD (pp. 157-178). New York: Guilford Publications, Inc.

Parto, J.A., Evans, M.K., & Zonderman, A.B. (2011). Symptoms of posttraumatic

stress disorder among urban residents. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease,199(7), 436-439.

doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3182214154

Plumer, B. (2012). Who receives government benefits, in six charts. The Washington

Post. Retrieved from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news /wonk/wp/2012/09/18/who-receives-benefits-from-the-federal-government-in-six-charts/?utm_term=.b5e815e2f824

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. (2017). American Psychological Association.

Retrieved from: http://www.apa.org/topics/ptsd/index.aspx

Prussing, E. (2014). Historical trauma: Politics of a conceptual framework.

Transcultural Psychiatry, 51(3), 436-458. doi: 10.1177/1363461514531316

The Heidelberg Project. (2017). Mission + vision. Retrieved from:

http://www.heidelberg.org/who_we_are/mission.html

Throsby, D. (2001). Economics and culture. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge

University Press.

Trauma (2017). American Psychological Association. Retrieved from:

http://www.apa.org/topics/trauma/index.aspx

United States General Accounting Office. (1989). Information on resident and

business relocation from poletown project (GAO/RCED-90-48FS).

Retrieved from http://www.gao.gov/assets/90/88598.pdf

West, S.D., Day, A.G., Somers, C.L., & Baroni, B.A. (2014). Student perspectives on

how trauma experiences manifest in the classroom: Engaging court-involved

youth in the development of a trauma-informed teaching curriculum.

Children and Youth Services Review, 38, 58-65.